Sunday in America has become the day we mourn the passing of the American middle class. The Los Angeles Times has published a long piece called “Rebuilding the Middle Class.” The title implies that we already know that the middle class has collapsed, which will come as a big surprise to most of the middle-class itself, which votes as though it believes that tax cuts and booming inequality has helped it thrive and grow, but never mind. The good news is that the columnist Joel Koktin and his co-author David Friedman at least see the problem, which is that the U.S. has become a “plutonomy” (a plutocracy?) in which the wealth of the broad population is of very little concern.

Their piece has some nice moments of telling the truth. “Since 1980, . . . Manhattan's inequality rate has risen from 17th to first among all U.S. counties. The richest 20% in the borough now earns 52 times what the lowest fifth does, a disparity roughly comparable with Namibia. Last month, just as Wall Street hailed record bonuses of more than $25 billion, thousands of New Yorkers lined up for 185 jobs — 65 of them full time — at the M&M's World theme store in Times Square.” The jobs pay a little under $11 a hour. It’s fun to wonder why Manhattan, the world’s headquarters of democratic capitalism, has the same level of income inequality as the world’s poor kleptocracies.

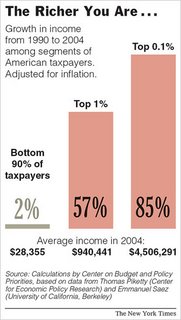

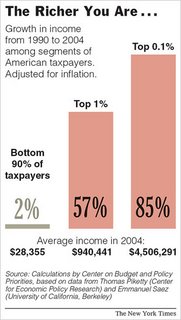

Koktin and Friedman state that “similar wealth concentration is occurring throughout the country.” This is most true of the coasts and the big cities where the wealthy especially like to live, for it is there that the working and middle classes find themselves in direct competition with the rich. My town, Santa Barbara, California, has seen the price of family housing driven up by people who can pay several million dollars for four or five bedrooms and a couple of shade trees in a dry climate. In most urban areas in California, a family earning the median can afford between a tenth and a fifth of the housing stock, all at the bottom end. Rents continue to rise because of pressure from people that would in the past have entered the ownership market. As wealth becomes skewed towards the top - “In Los Angeles County, 20% of the population pocketed about 55% of the region's income” - people in the middle get pushed down the food chain. The driver is the money that the top pulls in from everywhere else, nicely summarized by a couple of charts from recent issues of the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal.

In the first chart above, income increases are largely monopolized by the top. When we look at charts like this, we shouldn’t succumb to the myth that wealth is created by the top and then generously handed down to the rest of us. In fact wealth is created by everyone that works, and then much of it is skimmed through the thousand financial mechanisms and complex ownership positions that have become more sophisticated and less decodable over the last several decades. Whatever the means, the outcome is very plain.

Take a look at the second chart at the top. The economic “golden age” that followed World War II correlated directly with wider distribution of wealth. Today we’re almost back to the 1920s, where the concentration of wealth left the country’s social and physical infrastructure entirely unprepared for the depression of the 1930s.

I know that such correlations do not prove causal connections. But the intuition of a causal connection between broad prosperity and public services is becoming so widespread these days that opponents of government involvement in the economy - like Kotkin himself - are starting to change their tune. Rebuilding the middle-class here means nothing other than a large program of public projects. Kotkin and Friedman invoke a Democratic precedent - 1930s programs to organize “about 3 million workers, many of them unemployed, . . . to build roads, bridges and dams” - and a Republican precedent - Eisenhower’s 1950s “interstate highway system that, when completed, reduced travel times and made the economy more efficient . . . [and] also sparked an unprecedented growth in homeownership for working- and middle-class families.” We should do the same thing today, they say: these activities would be especially valuable in an economy that is losing even its high-tech middle-class jobs: “Despite enormous media and stock market hype, for instance, the U.S. has lost more than 700,000 information industry jobs since early 2001.” So the reconstruction of America would fix up a dilapidated country while generating hundreds of thousands of high-paying jobs, producing “more balanced economic growth.”

But here’s where Kotkin and Friedman’s piece crumbles like an L.A. sidewalk - at the very moment when you are asking yourself, “So are these erstwhile advocates of sunbelt business interests calling for government jobs?” You notice they never use the term “public works.” And you also know perfectly well that the same business system that has run down public infrastructure by campaigning endlessly for tax cuts and tax credits are not going to volunteer to start shelling out again. You know too that pro-business “moderates” like Arnold Schwarzenegger also want to rebuild - as long as they don’t have to spend new money. Arnold wants to borrow everything, and California citizens are now paying around twice as much every year for interest on their borrowed money as they spend on the University of California’s ten-campus system. Kotkin and Friedman go one step beyond our borrow-and-spend Governor: they want to pay for infrastructure through restored tax rates “tax breaks and incentives.” I am not kidding. These guys are going to give us a renewed public infrastructure by reducing public revenues. They are going to rebuild America by giving more public money to the businesses that have let it fall apart.

Excuse my rudeness, but this is exactly the kind of dumbass non-solution I expect from today’s middle-class policy people. These guys are smart enough to know that the middle-class depends on public services for its existence. But they are afraid to ask anyone to pay for the public services, maybe because thirty years of conservative polemics have cooked their brains. The outcome is always the same: continued deterioration leading to borrowing that doubles the cost of the public services that do about half the job.

If you are wondering why Kotkin and Friedman are afraid to offer more than their mini-me New Deal supplied by another round of tax breaks, you can read David Wessel’s “Capital” column in the Wall Street Journal for November 30th. Wessel chimes in by noting how even the Bush Administration’s Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and its recently-appointed Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke “warn that widening inequality threatens the political consensus for globalization, deregulation, and flexible labor markets, all of which they deem essential to economic growth.”

This means that they have figured out what the left, labor, et al have been saying for twenty or thirty years, but let’s not dwell on that - better late than never, right? Not this time. Wessel cites Clinton’s former labor secretary Robert Reich saying we need to “rebuild the middle class” through trade policy, industrial policy, stronger labor unions, anti-trust, public R&D, and the like, only so he can accuse Reich of “tried Democratic rhetoric.” If Reich is tired, what is fresh and new? It turns out it’s someone called Gene Sperling, who rejects “industrial policy” and “public works” - very original! - and then says the U.S. must become “a magnet for high-value job creation.” How? Well gosh, “it’s tough to say with confidence what will work because, given the global labor market” etc etc etc. In other words, Sperling has absolutely no idea what will work better than public works.

All the more reason for Wessel to tell us that the empty-headed Sperling is fresher than old, tired Reich with his actual suggestions for government action. For Sperling is a mentally paralyzed middle-class liberal who wants middle-class jobs but none of the functioning society that actually produces them, because a functioning society costs actual up-front money. The only thing Sperling knows is that industrial policy and public works are wrong. Therefore he can prove the point Wessel wants to make, which is that we have to HELP the middle class by keeping the same policies and the same prejudices that have DAMAGED the middle-class. That way, the rich can keep getting rich by quieting a potentially rebellious middle class without shareing more actual resources with them. Kotkin and Friedman know that they will no longer be seen as fresh and original advocates for the middle class the minute they suggest that the middle class should keep more of the money that, in fact, it actually earned in the first place.

This last idea is the big thing that’s missing from these pitiful efforts to help without helping. The middle class believes it is entitled to a certain status and comfort but not to the value of its labor, about which it is very confused. It doesn’t see that the rich’s money comes from their advantaged place in a system whose wealth is created by everybody who works. Every member of the system has the right to a system that works for them too, and not just for the people for whom it already yields the most. This is an extremely difficult concept for the middle-class, which learns in school and work that one’s merit is expressed not through a contribution to a larger system but through the income that one extracts from it. The working classes have a clearer sense that the value of their contribution is larger than what they gets back in income. The middle class can be defined as that group that believes in a general equivalence of the two, which means that Bill Gates really earned every dollar he has, and has no obligations to the society in which he earned it.

The same middle-class muddle ruled in the 1930s. During the Great Depression, this timid group mostly shunned even Keynesian solutions to its own predicament - government-created demand, meaning jobs, subsidies, the works - even as it sank further into the mire. What right did the middle-class have to government services when that would mean asking the rich to pay more for them? It was rescued from above by a card-carrying member of the top 0.01% percent, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, an American aristocrat who borrowed ideas from socialist and labor programs while the middle-class obediently lined up behind that classic examine of college-educated technocratic blindness, the Stanford engineer Herbert Hoover.

FDR understood something that is beyond the Right and the Middle in the U.S. today: society does not belong to rich people, who then include society at their discretion. Society belongs to everybody, and is created by all of them through their labor. The rich, who benefit from the efforts of society as a whole, are obligated to participate in making it function properly.

This insight was the origin of FDR’s Forgotten Man speech in April 1932. “It is said that Napoleon lost the battle of Waterloo because he forgot his infantry--he staked too much upon the more spectacular but less substantial cavalry. The present administration in Washington provides a close parallel. It has either forgotten or it does not want to remember the infantry of our economic army. These unhappy times call for the building of plans that rest upon the forgotten, the unorganized but the indispensable units of economic power, for plans . . . that build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.”

It is hard to imagine those who now speak for the middle class, the Kotkins and Wessels and Sperlings, being fresh enough to abandon Coolidge and Hoover for Roosevelt. But until they do, they will be not be helping rebuild the middle-class, but continuing to block it.